Source: https://www.trailforks.com/photo/17406309/

The Coeur d’Alene Lake/Silver Valley region’s unique cultural history, coupled with extraordinary recreational and environmental resources, makes this region of significance. Pre-European settlement, the Coeur d’Alene tribe, honed their trading abilities through extensive contact with neighboring tribes. Their trading prowess was so great that French fur traders who arrived gave them the name “Coeur d’Alene”, meaning heart of the awl. In 1860, gold was discovered in what would become known as Silver Valley. This discovery led to a rush of prospectors to the region, increasing tensions between the US and the Tribe. In a series of wars subsequent wars, the tribe’s land was taken. Ultimately, the Coeur d’Alene Tribe were left with less than 1/10 of their prior lands.

Silver Valley ended up being a poor source of gold, but rich in silver, lead, and zinc. Towns like Wallace and Kellogg grew quickly, as young men moved to attempt to strike rich. In its history, the CDL Mining District produced more than 1.2 billion ounces of silver, one of the top three largest amounts worldwide.

In 1910, the Great Fire rapidly burned three million acres, devastating many regional town and diverse ecosystems. 78 firefighters were killed trying to control the fire. Quick-thinking Ed Pulaski, saved 39 lives by leading his firefighters to an abandoned prospect mine. His ax design, now called the Pulaski ax, is standard issue for firefighters across the world.

In the last 30 years, mining and smelting has receded in importance to the local economy. Now, recreation and tourism are the economic drivers. An EPA Superfund for the Bunker Hill Smelter area is working to remove the toxic lead remnants, but has ignored the larger problem of heavy metal pollution further down the Coeur d’Alene River and in the lake.

All in all, the region’s different layers of cultural history add uniqueness to this stretch of beautiful Idaho wilderness.

Lake Coeur d’Alene:

The lake and its water are the heart of the region. Lake Coeur d’Alene is over 26 miles long with 135 miles of shoreline. It is the second largest lake in Northern Idaho. The lake is fed primarily by the Coeur d’Alene River and St. Joe River, while it discharges into the Spokane River through the Post Falls Dam. Before the dam, the “lake” used to consist of many smaller lakes. Now, the 40,600-acre reservoir has the capacity to store 223,100 acre-feet of water. Culturally significant species like the bald eagle, trout, kokanee salmon live in and around the lake.

Development and industry are in constant conflict with the lake’s sustainability and environmental protections. During the 19th and 20th centuries, mining companies dumped waste into the Coeur d’Alene River. This waste has migrated to the bottom of Lake Coeur d’Alene: there is now over 75 million tons of sediments polluted with lead and other heavy metals. This toxic waste remains inert given decent lake oxygenation levels because of the lake’s water chemistry.

Since the 1990s, the amount of annual phosphorus pollution has doubled, due to logging practices along the St. Joe River, increased development around the lake, and higher fertilizer run-off across the watershed. Extra phosphorus leads to algae growth, which reduces the lake oxygen levels, increasing the risk of heavy metals being released into the water table. In some of the shallower parts of the lake, oxygen levels are already dropping to near zero during the summer time. These areas luckily do not have high concentrations of lead and heavy metals in their sediments.

On-the-ground: Visit the lake! Many parks and vantage points will give you a good experience of what it has to offer, from Heyburn State Park in the southern end to Higgins Point on the northern end of the lake. From November to January, visit Wolf Lodge Bay to see bald eagles hunt spawning salmon.

Coeur d’Alene Mountains:

The Coeur d’Alene mountains, part of the Bitterroot Range of the Northern Rocky Mountains, play a key role in the climate and history of the area. The mountain’s highest peaks are between 6,000 and 7,000 feet, and the area is mostly covered by the Coeur d’Alene National Forest. The lake and valley sit on the windward side of the mountains, ensuring a lush, rain-filled environment. The mountains contain high amounts of silver, lead, and zinc. These minerals attracted miners who then formed the mining communities of Silver Valley.

Today, there are many dirt roads and trails that provide residents and visitors access to the secluded and expansive national forest. The mountains provide a great area for winter sports, and two ski resorts have opened in the Silver Valley, supporting the region as mining incomes have collapsed. Expansive vistas and beautiful paved trails also attract tourists from across the country.

On-the-ground: Settler’s Grove Interpretive Trail runs through an old cedar grove in a secluded part of the Coeur d’Alene Mountains. Along the trail are giant cedar trees that date back to when Columbus landed. It is only accessible by car via dirt road. Make sure you have a spare tire!

Source: https://goo.gl/maps/siPLNoXvDwdDdznM7

Great Fire of 1910:

The Great Fire of 1910 burned over 3 million acres of forest and is believed to be the largest wildfire in US history (Forest History Society). The fire burned much of Idaho’s National Forests, greatly reducing the area’s biodiversity and species count. It killed 87 people (mostly firefighters) and destroyed several towns–some of which never recovered.

The first of the smaller fires broke out on August 10 near Missoula, Montana in drought conditions. Soon, other small fires popped up across the Idaho panhandle region, western Montana, eastern Washington, and eastern Oregon. President Taft deployed 4,000 troops to the area to supplement civilian firefighting efforts, and these efforts proved successful in containing the fires. Then, on August 20, hurricane-force winds swept through the area, spreading the flames across the area and making fire-fighting efforts futile.

Ranger Ed Pulaski was trapped with forty-three men 10 miles southwest of Wallace, Idaho. Barely escaping the fire, he ordered his 43-man crew into an abandoned mine-shaft and threatened to shoot anyone who tried to leave. The party was overwhelmed by smoke, but when they woke up, all but five had survived. He was later credited with inventing the Pulaski axe, a common firefighting tool.

The Great Fire of 1910 shaped the national approach to forest management for a generation. The nascent National Park Service thought that they should stamp out little fires proactively to prevent another Great Fire. This policy has since been changed in favor of managed burning, as the accumulation of vegetation increases the risk of even larger fires breaking out.

The Great Fire of 1910 showed locals how powerful and dangerous nature could be.

On-the-Ground: The Pulaski Tunnel Trail near Wallace, ID memorializes Pulaski’s story, marking the route he and his men took and the mine shaft where they sheltered from the fire.

Vast Natural Landscape:

The region has abundant natural resources and space. The Silver Valley area has especially ample timber, silver, lead, and zinc. The original setters and communities relied on the extraction of natural resources, and many still rely on them today. The Idaho Department of Lands auctions off timber to local companies in order to raise revenue for its land management practices. Revenue is split between state public schools (largest portion), colleges, mental health hospitals, veterans homes, Capitol Commissions, and correctional facilities. In the 2019 fiscal year, 18,000,000 board feet and 2,000 poles of timber over 2,096 acres, amounting to millions in revenue and directly creating hundreds of jobs.

Silver Valley is one of the top three historical silver mining districts in world, having produced over 1.2 billion ounces of silver. Today, it has two active mines. The Galena Complex can produce up to 1 million silver ounces annually, given a high value of silver. In 2016, the Lucky Friday, mine, owned by Coeur d’Alene-based Hecla mining, produced 3.6 million ounces of silver. Museums and cultural sites attract tourists while preserving the mining culture and history.

Inside Lucky Mine: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1436&v=8TMLZr-nuVk&feature=emb_logo

The abundance of water has led to agriculture, fishing, and recreational opportunities in the Coeur d’Alene Lake watershed. East of the lake are many large wheat farms, although other crops and seasonal produce can be found. There are large populations of trout and salmon in the waters, allowing for plenty of recreational fishing opportunities. The lake is also very popular for boating, jet skiing, and other water-sports. Finally, Wolf Lodge Bay in the north eastern corner of the lake attracts bird watchers from November to January, as bald eagles come to hunt spawning salmon.

On-the-Ground: West of the lake off Route 95 are beautiful rolling hills of golden wheat and other agricultural activities. Take any of the back-roads that fork off (W Elder Road or ID-Route 58 are excellent because they are paved) heading towards the Washington border. You will amazed at the gently rolling fields of wheat in all directions.

The Tribe:

The modern Coeur d’Alene Tribe is the “sum of uncounted centuries of untold generations” (CDA Tribe Website), and they have lived across the region for thousands of years. The tribe, in their own language, is called the Schitsu’umsh, or “the discovered people”. The Tribe’s other name came from late 18th century French fur traders, who referred to the tribe as “Coeur d’Alene’s,” meaning “Heart of the Awl”, because of their trading prowess.

The Tribe has sovereign authority over 345,000 acres on their reservation, a fraction of their historical territory of 3.5 million acres. Much of the territory was taken by the US government during the Skitswish War of 1858, and a 1873 treaty established a Coeur d’Alene Reservation. Its original 600,000 acres has since shrunk to its current size due to US legislation. A 2001 US Supreme Court ruling upheld the Tribe’s rights to ⅓ of Lake Coeur d’Alene, forcing regional stakeholders to work with the Tribe on Lake restoration and pollution mitigation efforts. Current tribe enrollment is around 2,190 members.

Founded in 1993, the Coeur d’Alene Casino provides over $20 million annually for the tribe’s activities, including fighting for environmental causes , supporting Benewah Medical Center, and funding the tribal school, whose offering include a college degree program in cooperation with a local state school.

On-the-ground: Drive through Plummer, the reservation, and the casino (if interested) to see a little bit of the Tribe today.

State of Idaho:

The State of Idaho plays a dominant role in the region, as it sets the laws, implements policy, and invests in governmental priorities. Politics is dominated by the Republican Party in both the region and state, although a large unaffiliated population does exist. Northern Idaho has its own distinct climate, culture, time zone, and economic hub, compared to the rest of Idaho. Boise, the state capital, is seven hours south of Coeur d’Alene by driving (to put in context, Seattle is a 5 hours from Coeur d’Alene). The State of Idaho tends to promote regional development, tourism, and free market ideals over environmental preservation, labor rights, and large government. The state Department of Lands engages in natural resources sale (timber, minerals, oil/gas) on its state lands to support Idaho schools. Idaho has one of the lowest overall state tax rates in the US (for median US household).

There has been high amounts of tension between the Coeur d’Alene Tribe and the State of Idaho over Lake Coeur d’Alene management. The Tribe seeks more restoration efforts from the mineral and mining pollution, while the State seeks to expand a fledgling tourism and recreation industry.

On-the-ground: Driving along the shoes of Lake Coeur d’Alene, one will see extensive development–golf courses, large houses, and docks where natural ecosystems used to be. Economic development brings jobs, tourism, and wealth to the region, at the cost and risk to the environment. Of particular concern is the potential for fertilizer run-off catalyzing the death of the Lake (increased nutrients leads to algae blooms, which suck the oxygen out of the water, allowing mineral pollution which is dormant at the bottom of the lake to rise and mix throughout the water column).

Source: https://parksandrecreation.idaho.gov/parks/heyburn

The Federal Government:

Although seemingly disconnected to the independent and sparsely populated area, the Federal Government continues to have significant influence over the region through its management of national forests, resources, and environmental protection. National Forests (managed by the US Department of Agriculture) account for a large part of the Lake Coeur d’Alene/Silver Valley regions’ area and resource extraction is still a driver of the economy.

Tightening EPA standards on acceptable lead levels in the 1970s and 1980s contributed to the demise of Bunker Hill Lead Smelter, with the plant closing in 1982. The EPA has since received millions in damages from mining companies and industry to fund clean up of lead and mine tailings in the surrounding land and river. The EPA is currently building a filtration plant for the Coeur d’Alene River to reduce downstream zinc pollution. The State of Idaho, the Coeur d’Alene Tribe, and local residents want money and investment to align with their own interests, making the clean-up process contentious. The EPA has decided to leave Lake management up to the State and the Tribe, concentrating its resources to clean up populated areas upstream of the Lake.

On-the-ground: Visit the Coeur d’Alene National Forest, which stretches from Silver Valley to almost the Lake. One can explore the secluded ranger trails, by foot or car, that go deep into the mountains. Or visit the EPA clean-up efforts in Smelterville, and see the work that has occurred since efforts began over a decade ago.

On-the-ground: Visit the Coeur d’Alene National Forest, which stretches from Silver Valley to almost the Lake. One can explore the secluded ranger trails, by foot or car, that go deep into the mountains. Or visit the EPA clean-up efforts in Smelterville, and see the work that has occurred since efforts began over a decade ago.

Source: https://www.facebook.com/CDAbasin/photos/a.253057834812059/2835033179947832/?type=3&theater

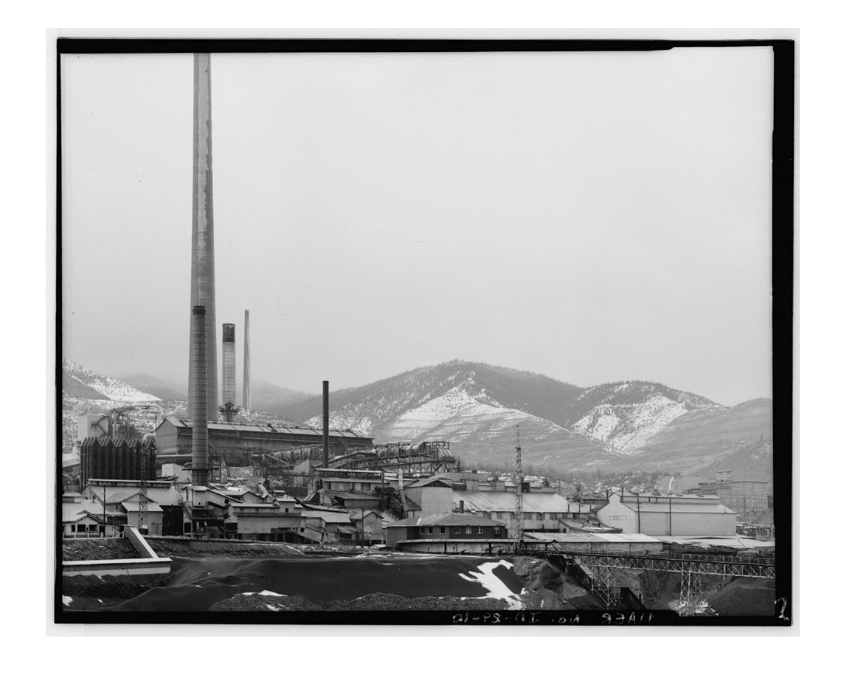

Bunker Hill Smelter:

The Smelter symbolizes the changing identity and priorities of American society. Created in 1917, the smelter was built to process the vast amounts of lead being found in surrounding silver and zinc mines. The smelter was very profitable and brought many additional jobs to the region, but also significantly increased hazardous pollution. Much of the smelter waste was dumped into the nearby Coeur d’Alene River, which poisoned much of the downstream area. Over 75 million tons of pollution sits at the bottom of the Lake. The plant also belched large amounts of lead particles into the air. In 1973, a fire destroyed the Bunker Hill baghouse, the main pollution-control system, yet the plant continued to operate for the next year and a half. These particles landed across Smelterville and Kellogg, poisoning generations of residents. Children in Kellogg were testing an average 50 micrograms per deciliter of blood–10 times what CDC considers high enough to warrant concern and higher than the 45 microgram level where they advise chelation therapy to remove heavy metals from the bloodstream. In 1982, the smelter closed, citing lack of concentrates and a stricter EPA lead air pollution limit. At that time, it had grown to be the largest lead smelter in the world. Now, it is one of the largest EPA Superfund sites in the US.

On-the-ground: Visit the land where the smelter used to sit on, between Kellogg and Smelterville (see Quest for more details).

Source: https://www.loc.gov/resource/hhh.id0251.photos/?sp=2

Mines of Silver Valley:

Gold was first found in the region in 1860. This brought a wave of prospectors, who found some gold in creeks across the area. The primary metals turned out to be silver, zinc, and lead, with massive quantities: over 1.2 billion ounces of silver, 3 million tons of zinc, and 8 million tons of lead, ranking the valley as one of the top ten mining districts of the world (and one of the top three greatest silver mining districts). Veins of Galena (lead sulfide) contain Sphalerite (zinc) and tetrahedrite (silver) within them. Regional communities like Wallace and Kellogg were founded due to the abundance of mining activity in the area.

There has always been tension between workers and corporate leaders, with poor working conditions and union busting. In 1892, strikes erupted demanding a living wage for all workers, both skilled and unskilled. Activism here led to the creation of the Western Federation of Miners in 1893. In 1899, Bunker Hill Mine management fired 17 employees suspected in attempting to create a union, and tensions boiled over once again. Around 150 unionists seized the mine’s tramway in Kellogg, while another 1,000 miners gathered from across the area. These miners blew up the Bunker Hill office, company boardinghouse, and concentrator, which was one of the world’s largest at the time. President McKinley sent the majority-black 24th Infantry regiment to round up all the men and put them in “the bullpen” for weeks of physical punishment. In 1905, Governor Steunenberg was assassinated because of his role in the 1899 arrests. Still, safety remained poor and wages low, as much of the profits went to company investors. In 1972, 91 men died in Sunshine Mine from carbon monoxide poisoning, leading to increased safety protocols and checks in mines nationwide.

On-the-ground: Check out the Wallace District Mining Museum or the Sierra Silver Mine Tour to see what a Silver would have looked, sounded, and felt like.

Source: https://www.spokesman.com/stories/2009/oct/20/amid-silvers-steady-rise-sides-fight-over-mine/

Trails:

Trails are a key way the residents of the region connect with their natural surroundings. Many transportation routes were first identified by the Coeur d’Alene Tribe, which used trails to move from settlement to settlement. For example, I-90 directly follows an old trail route through the mountains. Many modern day trails, like the Route of the Hiawatha, are considered rail trails, as they follow old railroad routes. Another prominent rail trail, the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes was named one of the top 25 trails in the US by the Rails to Trails Conservancy (2010). It runs for 73 miles, much of it along the scenic Coeur d’Alene River. Other major recreational trails include the North Idaho Centennial Trail (24 miles), which runs from the border of Washington to Higgins Point, connecting the cities of Spokane, Post Falls, and Coeur d’Alene to natural areas by bike or foot. Access to nature play a key part in the experience of living in the region.

On-the ground: Rent a bike and ride some of the trails! The Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes is especially scenic, crossing Lake Coeur d’Alene, following the Coeur d’Alene River, and meandering across Silver Valley.

Source: https://parksandrecreation.idaho.gov/parks/trail-coeur-d-alenes

The city sits on the northern shore of Lake Coeur d’Alene and provides the economic anchor for the otherwise sparsely populated region. The Coeur d’Alene/Post Falls metropolitan area is the third largest in Idaho with around 90,000 people, and the Coeur d’Alene city limits are estimated to have a population of 50,665. Several mining firms are headquartered in the city, including Hecla Mining. Couer d’Alene had a number of museums and cultural sites, including the Museum of North Idaho, which documents the history and culture of the region and city. The city has great access to the outdoors, with the Coeur d’Alene City Park, Tubbs Hill and beach, Fernan Lake, and the Couer d’Alene Resort Golf Course (the only golf course in the nation with a floating hole) within its immediate vicinity. In 2009, the city was ranked the 12th most “Uniquely American City or Town” by Newsmax magazine because of its small-business friendly environment and embracing of its natural beauty.

On-the-ground: Tubbs Hill has remarkable hiking trails that lead to a beautiful, secluded beach. It is definitely worth the visit if you would like to go for a walk, while being close to the amenities of downtown Coeur d’Alene.

Three Ways to Get Involved:

- Travel to the Region: Elements of the Lake Coeur d’Alene/Silver Valley Region cannot be recreated on a screen. The vastness of the land, smell of the trees, and connections with local residents are all lost in screen content, Especially in a relatively rural area like this region, many gems are even out of cell-phone service!

- Learn more about and advocate for lake clean-up: The EPA refuses to spend money from settlements with mining companies on clean-up efforts that do not directly impact human life right now. It is incredibly short-sighted and unfair to leave the cost on the Tribe of the Coeur d’Alenes, who did not receive compensation for the stealing and pillaging of their homelands. Advocacy can take place with your friends, your congressional representatives, or through the EPA directly

- Take a closer look at your own surrounding: This page contains a lot of information about the Lake Coeur d’Alene/Silver Valley region. It hopefully distilled the region’s essence through stories, places to visit, and keys of significance in order to lay the foundations for a potential National Heritage Area (NHA) proposal. Your community or a community you know of could be another area that could benefit from NHA status. Collect, organize, and share the story of a region close to your heart! You will be contributing to the safeguarding of culture and history for future generations, an aim of the NHA movement. Once you have an understanding of your own area, you could connect with others who are working on fostering partnerships and collaboration in the Lake Couer d’Alene/Silver Valley region.

A Regional Comparison to the Calumet Region of Indiana and Illinois

The Lake Coeur d’Alene/Silver Valley region shares a number of similarities to the Calumet region we have been studying in class. First the regions’ respective lakes have significant impact on their economic strength, culture, and quality of living. Without Lake Michigan, the Calumet region would not have been so attractive to factory owners, as transportation by boat was key for shipping finished steel products to Detroit and the world. The Indiana Dunes beach is nationally recognized in its beauty and biodiversity, as well as locally renowned for being an excellent beach. Much of the recreational activities use Lake Coeur d’Alene in some form, whether that be the beach, fishing, boating, or bird watching. Along with agricultural, recreational activities and summer tourism are crucial to the valley’s economy.

Both regions also face significant environmental challenges due to their extraordinarily large dirty industry presence. In the Calumet, the main industry has been steel mills and oil refineries. Factory owners leveled dunes and dumped industrial waste into the surrounding swampland, to the point where rivers could catch on fire and organisms that fell in would die. Even recently, thousand of fish died in the Little Calumet River and Lake Michigan due to the accidental release of cyanide and ammonia by ArcelorMittal. In Silver Valley, the main industry has been mining and lead smelting. Here, factory owners blew up hills, spewed lead into the air, and dumped toxic mine tailings into the Coeur d’Alene River, turning it florescent green. Even after years of EPA cleanup, lead poisoning downstream paralyzes migrating tundra swan, causing them to slowly die by starvation in a land of plenty. 75 million tons of sediment contaminated with heavy metal sits at the bottom of Lake Coeur d’Alene–a ticking time bomb with current rates of development.

Both regions experienced significant loss of jobs and livelihoods due to the decline of the polluting industry and are trying to replace it with tourism and services-economic activity. The Calumet region lost large amounts of jobs from the shuttering of steel and auxiliary industries. The region is trying to leverage the Indiana Dunes National Park to attract visitors from across the country and Chicago to bring jobs back to the community. Many of the Lake Coeur d’Alene/Silver Valley region’s mines and the smelter closed in the 1970s and 1980s due to increased environmental standards, low mineral prices, and disagreements between labor and management. Since, the region has diversified its economy with cultural tourism in Wallace/Kellogg, new ski resorts and trails, a casino, and recreational activities on the lake.

Some quick differences:

The Calumet region is much more dense than the Lake Coeur d’Alene/Silver Valley area.

The Calumet region is attached to a large metropolitan area, Chicago, while the Lake CDL/SV area is not.

The Calumet region historically has much more collaboration among regional partners than the Lake CDL/SV region. The Calumet region has been able to put together a proposal for a National Heritage Area encompassing parties ranging from industry to environmentalist. The Lake CDL/SV region struggles to even make decisions about what the priorities of federal dollars should be, how to manage the lake’s worsening pollution problem, and even who has power to argue (Supreme Court case: Idaho vs. United States reaffirmed the Coeur d’Alene Tribe’s control over 1/3 of the lake).

Reflections:

To begin, thank you to Professor Mark Bouman and Shannon Morrissey (TA) for teaching the class Planning for Land and Life. This project and website would not be up if it wasn’t for the class materials, usage of the Calumet National Heritage Area as a case study, and assignments to provide structure to the pages. Thank you to all the in-class speakers who shared their work and knowledge about the Calumet region–it was very interesting to hear such a diverse group of perspectives on a common area.

Over the course of this crazy quarter–maybe even the craziest quarter of the University’s history (knock on wood), I have learned a lot about both the Calumet and the Coeur d’Alene Regions through extensive readings, lectures, and experiences. It was refreshing to leave the “ivory tower” of theory and philosophy to move into the more tangible aspects of understanding a place and the elements and people that comprise it. I hope to revisit both the Calumet and Lake Coeur d’Alene/Silver Valley Region to greater appreciate the areas, with my newfound knowledge.

I have also learned how to create rudimentary websites via WordPress! I have never built a website before, so this project was somewhat challenging at first, but very exciting. I am sure that I will use this skill sometime in the future.

In creating this list, I thought about my own brief experiences in the Lake Coeur d’Alene/Silver Valley region. I visited the area with Paulette Jordan while working on he campaign for Governor of Idaho. Paulette is a member of the Coeur d’Alene Tribe and a local of the area–I’ve been to Heyburn State Park, Coeur d’Alene, and areas around the lake, but have not been up into the Silver Valley area. So this project was super interesting, as it was a place I knew, but also did not really know. Anyways, I hope you enjoy the website, and please let me know if you have any questions!